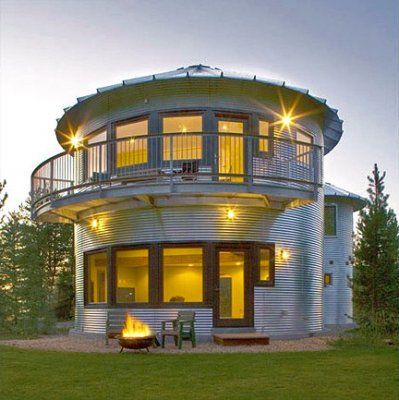

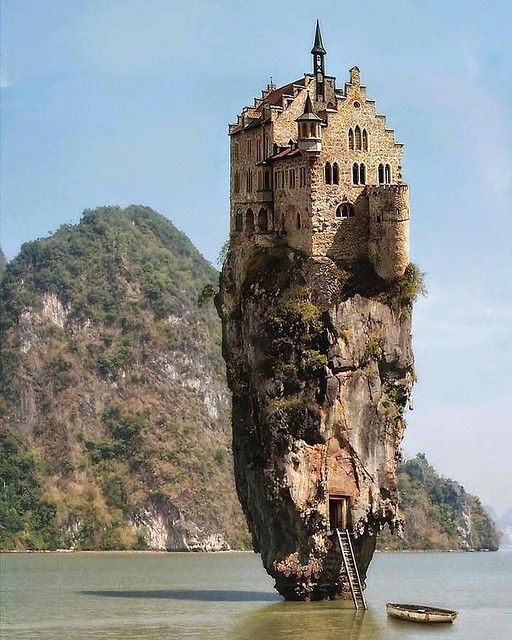

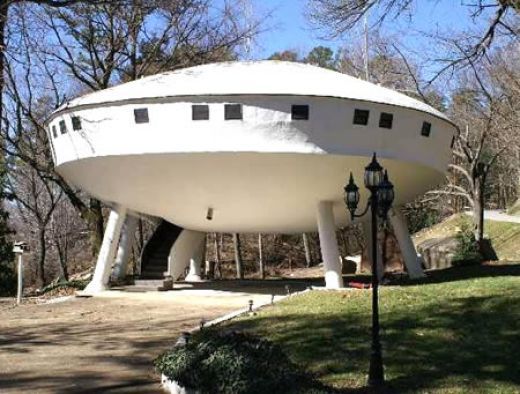

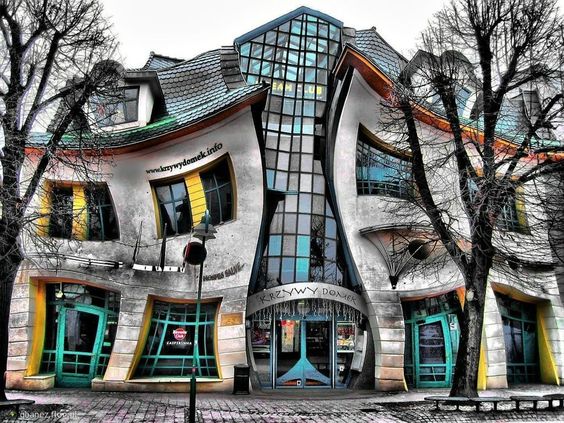

Some people like to go against the flow of a normal house! I like the house which the front porch tips up and becomes a garage and the mirror house. Some my call them crazy homes!

Marvel of Peru

Another one of my favorite flowers are blooming now: Four o’clocks or Marvel of Peru. It is an unusual plant, in that it may produce flowers of different colors on the same plant—including white, yellow, and a variety of pink, red, and magenta colors. Individual flowers may also feature a mixture of colors. The plant can be expected to bloom from mid-summer all the way until frost.

They typically bloom in the late afternoon, from about 4:00 to 8:00 pm, although on cloudy days they may not close at all. Since four o’clocks bloom in the evening, plant them where you’re sure to see them and catch a whiff of their fragrance. They mingle and grow through other plants nicely, making a nice underplanting. Hummingbirds will visit your garden because they are attracted to four o’ clock’s tubular flowers.

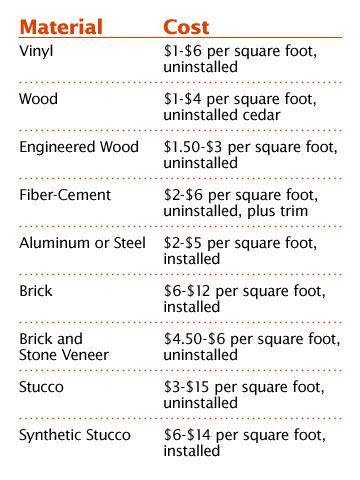

Exterior siding for your Home

Exterior siding for your home is the first line of defense against the elements and the first thing buyers see from the curb. From brick to stucco to vinyl to wood, there are a number of different options for your next build. Here are the advantages and disadvantages of the seven most popular varieties.

Vinyl

The pros: Relatively inexpensive and quite versatile, vinyl can be installed over existing materials, making it a nice retrofit option. Since it’s easy to handle, it can also be installed quickly, which can help reduce labor costs. Modern vinyl is also available in a variety of colors and textures, which can mimic wood shingles, wood-grain lap siding and even stone.

The cons: While promoted as a maintenance-free material, vinyl siding does require some work. Mold and grime can build up on the surface. Vinyl is also vulnerable to weather damage, which may result in occasional repairs. Since the typical panel is 12-feet long, the ends require overlapping, which results in seams. Extra-long panels are available; however, they cost about 30 percent more than standard-length panels.

Wood

The pros: Easy to cut, shape and install, wood siding is prized by designers and homeowners for its natural aesthetics. Whether it’s board and batten, shakes, clapboards or shingles, there are an array of wood species and grades to consider. Quality wood siding can last decades with proper maintenance.

The cons: Quality wood grades cost a lot, and the siding will always demand diligent maintenance. Wood siding is also vulnerable to woodpeckers, termites and rot.

Fiber Cement

The pros: A mixture of clay, cement, pulp and sand, fiber cement has a strong reputation for low maintenance and stability. It can be made to mimic stucco, shingles, masonry and wood clapboard. It’s also easy to paint and available in a diversity of attractive finishes. Fiber cement siding is termite-proof, fire-resistant and comes with a 30-year warranty.

The cons: Because it is so heavy, fiber cement requires special installation tools and techniques, which can drive up building costs. After about 15 years, it usually needs to be refinished; however, maintenance duties are virtually nonexistent otherwise.

Stucco

Pros: Valued for its durability and unique aesthetics, stucco includes epoxy, which helps to prevent cracking and chipping. Well-maintained stucco can last a lifetime, especially in drier parts of the country.

Cons: Because it usually requires three coats, stucco siding can drive up labor costs. It’s also not an ideal option in wetter climates; however, with proper application techniques, it is still a viable option.

Engineered Wood Siding

Pros: Made from exterior-grade resins and wood fibers, this siding material is strong enough to tolerate the most extreme weather conditions. It’s available in a nice variety of textures and styles, such as rough-sawn clapboard, beaded lap and wood shingles. It also usually comes primed and ready to paint or with existing factory finishes.

Cons: While currently backed by iron-clad warranties, earlier versions have prompted class-action lawsuits, due to moisture issues. Many builders feel the modern varieties haven’t been on the market long enough to prove reliable.

Brick

Pros: Masonry offers substantial aesthetic appeal, along with impressive durability. It requires very minimal maintenance and typically lasts the life of a home. Brick is also resistant to fire and won’t mold or rot.

Cons: Since masonry veneer is non-structural, builders must tie it back to the building structure to prevent movement under weather and earthquake loads. It’s also expensive, compared to most other siding options. Color options are also somewhat limited.

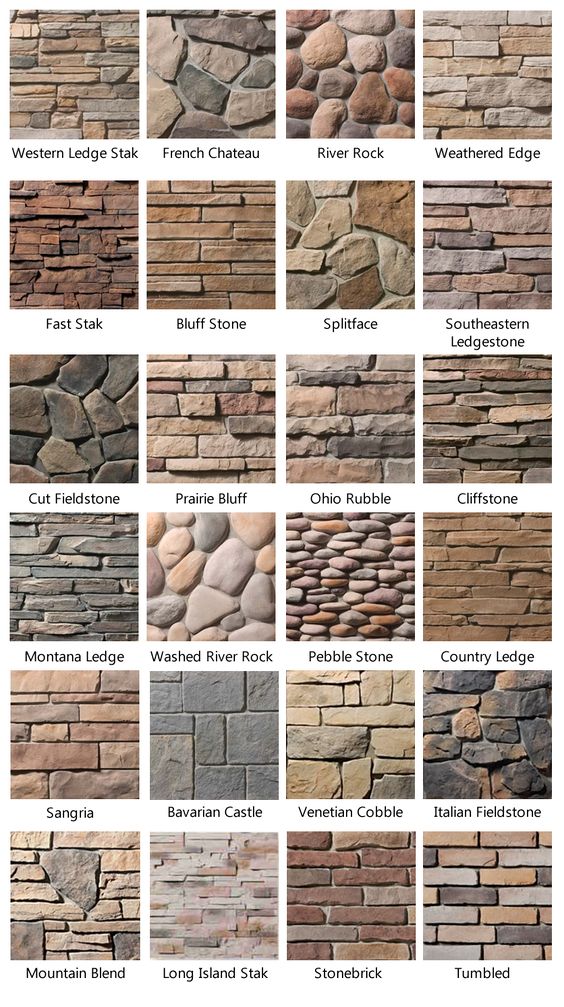

Synthetic Stone

Pros: Made inside molds from a mixture of sand, cement and aggregate, synthetic stone siding can mimic virtually any stone type, including limestone and granite. While rarely used to cover an entire home, it makes a great accent on chimney exteriors and lower portions of walls. Synthetic stone looks very similar to real stone at a fraction of the cost. Because it’s lightweight, there’s also no need for builders to reinforce foundation footings.

Cons: While it does cost much less than real stone, synthetic stone is still quite expensive relative to other siding options. Also, because it is made of concrete, synthetic stone is less structurally sound than actual stone.